The Kremlin’s reaction to the pandemic is part of a blame game. However, it remains to be seen whether Putin will be the winner in the long run.

With around 500,000 confirmed cases of Covid-19 by mid-June, Russia ranks third in the world after the United States and Brazil. But the Covid-19 pandemic was only one among multiple major challenges the Russian executive had to deal with in early 2020, these are: First, the largest overhaul of Russia’s constitution since 1993. Second, the oil price collapse in the wake of the Russian-Saudi Arabian oil price war and dwindling demand on the world market. And, third the pandemic itself. As these three crises interacted with and reinforced each other, they appeared to amount to a perfect storm for President Vladimir Putin who had just embarked on his third decade at the helm of the Russian state. The main goal of the constitutional reform was an amendment that would zero Putin’s current presidential terms and would therefore allow him to run again as president in 2024 for another two six-year terms until 2036.

The climax of this hasty constitutional reform was a plebiscite scheduled for 22 April that was conceived to bring a major legitimacy boost to Putin. The presidential decree that set the date for the plebiscite on 22 April was published on 17 March, on 25 March, however, the plebiscite was canceled for the time being due to the pandemic. In the course of this week, the risk calculation of Russian leadership apparently changed. Infighting between the Presidential Administration determined to hold the constitutional plebiscite before introducing measures to curtail the virus and the Mayor of Moscow Sergey Sobyanin who insisted on an immediate and comprehensive lockdown delayed decision-making on nation-wide measures. On 25 March, during his first address to the nation Putin announced non-working days as of 28 March. By the end of March, most Russian regions had some form of stay-at-home measures in place. Moreover, the shock of the oil price which on 21 April temporarily reached $12 — just as in the year 1999 when Vladimir Putin assumed the role of PM — certainly also had a major impact on the strategy to support the economy during the lockdown. With an expected contraction of over 5% of real GDP in 2020, the fiscal stimulus in the wake of the lockdown amounts to just 3% of GDP. From the perspective of the Russian leadership, the pandemic was a short-term minor nuisance compared to low oil prices in the long run: Russia’s rainy day fund – primarily the National Welfare Fund – was to be used mainly to compensate for shrinking revenues from natural resources to the state budget and to be spared for future major shocks.

Given the upcoming electoral cycle of the 2021 parliamentary and the 2024 presidential elections, an even faster depletion of the National Welfare Fund than the projected three years due to a more lavish fiscal stimulus package in the wake of the pandemic does not seem to be on the table for the Kremlin. President Putin’s announcement of the government’s gradual exit strategy from lockdown as of 12 May appears premature due to approximately 10 000 infections per day around that time. Despite the obvious risks, it was only early easing that would allow the Kremlin to go ahead with the constitutional plebiscite, and to reduce the pressure from the economy and population to increase the fiscal stimulus. On 1 June, Putin set the date for the constitutional plebiscite for 1 July, just one week after the Victory Day parade also postponed from 9 May to 24 June. What the crisis management exposes is the shifting of responsibility and blame away from president Putin to other actors and state bodies in the federal and regional government, and it exposes previously known elements of bad governance, but not necessarily an apparent weakness of Putin (yet) or imminent danger for the regime.

The executive weakened by the virus

On 30 April, the Russian prime minister Mikhail Mishustin declared on live TV he was diagnosed with Covid-19 and will need hospitalization. The same day, President Vladimir Putin signed a decree to appoint Mishustin’s first deputy Andrey Belousov as interim PM. This chain of events is remarkable for at least two reasons: First, it was only the second time in Russia’s post-Soviet history a top executive official temporarily resigned from his duties due to a medical condition. To date, interim PMs were only appointed in the wake of dismissals of the whole cabinet. The last (and only time) a comparable situation occurred was in late 1996: After having suffered from several strokes including one in the midst of two presidential election rounds, president Yeltsin stepped down on 5 November 1996 to undergo heart surgery only to resume office 23 hours later.

But it was not only PM Mishustin who was diagnosed with Covid-19: At least three ministers (Yakushev (construction), Fal’kov (science and higher ed) and Lyubimova (culture)) as well as President Putin’s long-time press secretary Dmitry Peskov contracted the virus and had to undergo medical treatment. Most importantly, even though Putin had not contracted the virus, he went into permanent self-isolation at his residence in Novo-Ogarevo after it became know that chief physician of Moscow’s main specialized Coronavirus hospital Denis Protsenko announced on 31 April he was diagnosed with the virus. Putin had visited the hospital a week earlier on 24 April and was in close contact with Protsenko without protective gear.

Second, Mishustin’s infection was only slightly more than 100 days after he was appointed PM on 15 January. As a rule, PMs are dismissed and (re-)appointed in the course of presidential elections as new cabinets take office after presidential, and not parliamentary elections. Mishustin’s predecessor’s cabinet headed by Dmitry Medvedev had only been appointed in May 2018, and the last time a PM had been appointed in the midst of a presidential term was in 2007. Therefore, initially speculations abounded whether Putin would take Mishustin’s infection as a pretext to get rid of a PM not fit to steer Russia through the pandemic. Both an ailing executive leadership and a potentially imminent cadre carousel in the cabinet were reminiscent of Yeltsin’s crisis governance in the late 1990s. Nonetheless, even from hospital Mishustin demonstratively took part in operative management, and on 19 May Belousov’s interim premiership was terminated by presidential decree: Mishustin (like all other ministers) was back from the sickroom.

Crisis management without declaring the state of emergency

Many states around the world declared a state of emergency (SOE) to cope with the pandemic. Russia did not, and the reasoning is straightforward: President Putin and the government had little to gain and much to lose from a SOE. Preliminary research demonstrates that autocracies were less likely to introduce SOE than democracies during the pandemic. Russia, therefore, fits the international pattern: executives in non-democracies already amassed vast powers and can act largely unconstrained from the legislature or the judiciary.

The system of emergency measures in Russia is hierarchical and features three main levels: Low: heightened state of readiness; middle: emergency situation; and high: state of emergency. While some regions including the capital city Moscow declared a heightened state of readiness, no further measures were taken by the federal executive. It did expand its powers, though, without using them yet: On 1 April, Putin signed a law that gave the federal government additional powers to call an emergency situation in the whole federation or in parts of it when a dangerous disease spreads. Moreover, the Governmental Commission for the prevention and liquidation of emergency situations headed by Emercom Minister Zinichev could have upgraded a regional emergency situation declared by governors to a federal one. Finally, quarantine measures can be introduced by the federal or regional governments on a recommendation by the Chief sanitary doctor as per a law on sanitary protection. Despite these vast competences of the presidency and the federal government, none of these measures were actually introduced. In fact, already the official discourse meticulously avoided terminology associated with legislation on emergency measures. Citizens were forced to obey “self-isolation” and “non-working holidays” (in theory with no cuts to the salary), but no quarantine or regular short hours were introduced.

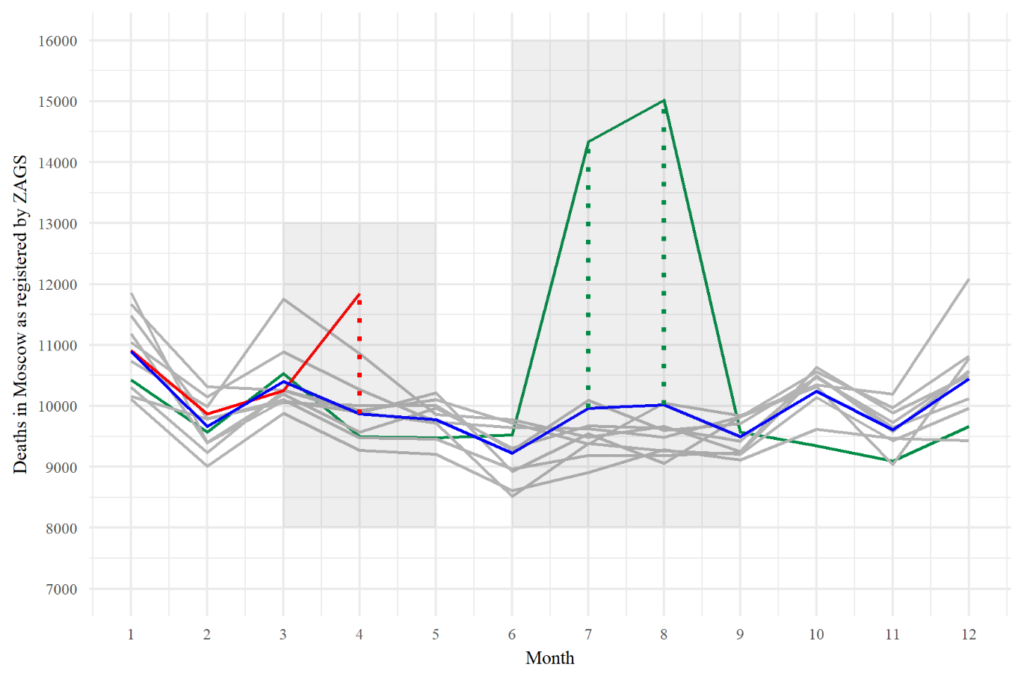

Not just opposition activists and lawyers criticized this approach, even members of the loyal upper chamber of the Russian assembly – the Federation Council – acknowledged measures were taken “under complete legal indeterminacy”. Beyond the obvious observation that the Russian federal executive can act unconstrained even without declaring emergency measures, there are several other reasons that need to be taken into account: First, state of emergencies are generally rare and so far remain an executive measure of the 1990s. On 3 October 1993, Boris Yeltsin declared a SOE in Moscow in the wake of the constitutional crisis between the executive and the legislative. All other SOE in the years between 1991 and 1995 related to secessionist and ethnic conflicts in the North Caucasus. Emergency situations are declared much more frequently, and the degree of severity depends on the damage disasters such as floods, wildfires, storms and other cataclysms inflict: a federal emergency situation is declared when more than 500 persons suffer and the material damage exceeds 500 million rubles. As a rule, emergency situations are declared by regional authorities and may be later upgraded to federal status by the Governmental Commission or by the president. The latter occurred in 2019 in the wake of heavy floods in the Irkutsk region. The last time a Russian president declared a federal emergency situation was in 2010 by president Dmitry Medvedev in the seven regions Marii El, Mordoviya, Vladimir, Voronezh, Moscow region (not the capital city), Nizhnyi Novgorod and Ryazan due to large-scale wildfires. The 2010 wildfires indeed might be the one natural disaster the current crisis management of the executive could be judged against. Early on, the death toll of the wildfires was estimated to be around 55,000 while a subsequent analysis based on more fine-grained data found an excess mortality of 11,000. Early estimates of Covid-19-related deaths in the City of Moscow based on data by the city’s Civil Registry Office (ZAGS) demonstrate an excess mortality of about 20% or 1800 deaths in April 2020 compared to the average in the last 10 years (red line). As Figure 1 also demonstrates, excess mortality so far appears to be much higher in July and August 2010 as a result of the wildfires (green line). But Moscow mayor Sobyanin already warned on 22 May that excess mortality will be much higher in May than in April.

While the death toll from Covid-19 will remain a hotly disputed issue due to data manipulation, it appears that both in terms of human and material damage, an emergency situation in parts of Russia could have been easily justified. Second, it might be argued that SOE or emergency situations are highly unpopular among the Russian population, and Putin didn’t want to inflict more damage to his plummeting approval ratings. This argument remains doubtful at least for the early phase of the pandemic. According to a survey from mid-April by Gallup International, 65% of respondents would have supported a strict quarantine or a SOE. But the attitude of Russians quickly changed: One month later in mid-April, 64% of respondents of a representative online survey supported easing of lockdown measures, only 23% spoke out in favor of continued restrictions. As SOE are declared for 30 days, the measure could have been easily reviewed in the light of public sentiment over time.

Third, the Russian government had direct interest in maintaining legal ambiguity for financial reasons. According to Pavel Chikov from the rights group Agora, both private persons and legal entities would be entitled to compensations of losses and damages for harm inflicted by the pandemic according to the respective laws on quarantine and emergency measures, but not due to “heightened readiness”. Small and midsize businesses have been especially vulnerable during the lockdown, and unemployment has risen to officially registered 1.7 million, and 4.3 million in total according to Rosstat surveys. By refraining from declaring a SOE, an emergency situation or quarantine, the Russian government retained flexibility in terms of when and whom to support with crises relief measures, for example doctors, medical workers of families with children, instead of being forced into compulsory payments. The City of Moscow already faced a class action lawsuit for the alleged restriction of rights during stay-at-home measures, and more across Russian regions are likely to follow. The presidency and the government dodged responsibility so far.

Short-term decentralization as a technology of governance to shift responsibility and blame

The Russian Federation is a highly centralized federal state. Therefore, when on 2 April president Putin ostensibly transferred some powers to regional governors to fight the pandemic by decree, many observers interpreted this alleged decentralization as weakness: President Putin did not want or could not impose centralized countermeasures to fight the pandemic. The problem with assessments whether some form of decentralization occurred and how it should be interpreted in terms of executive power is twofold: First, clear criteria are needed for interpreting what decentralization means for executive politics in authoritarian regimes. On the one hand, research demonstrates that two dimensions are necessary for successful crisis management: governance capacity and governance legitimacy. As for capacity, specialization in formal governance structures is thought to be beneficial to crisis management. In terms of federal specialization, a certain decentralization is believed to facilitate a self-organized response to crises. In the Russian context, a decentralized response to crisis management appeared unexpected both due to the high degree of centralization of the federation with its heavy-handed top-down management style and the related incentive system for governors to dodge responsibility, and due to the constitutional amendment process during which Putin demonstrated leadership. Hence, while zeroing term limits signaled a further personalization of power, a decentralized response to the pandemic could be interpreted as a sign of weakness and degradation of presidential power.

Second, to make sense of the Russian alleged decentralized response to the crisis one would need a clear understanding of what the concept of decentralization entails. One (Treisman, Schneider) prominent conceptualization distinguishes between administrative, fiscal and political decentralization. Among those three indicators, only a short-term political decentralization within a tight framework set by the 2 April presidential decree occurred. It was prolonged on 11 May, but with further demands to coordinate with the federal government. Administratively, the regions remained subordinate and therefore dependent on the federal center. The fiscal measures of the central government such as a moratorium on repaying federal budget loans for the year 2020 or additional financial support for regional budget balance is likely to increase regional dependence even further.

As Regina Smyth et al. show in their policy paper, political decentralization and regional solutions might even be required as both the threat posed by the pandemic as well as the resources available to the regions such as economic sustainability, the prevalence of pensioners, the availability of doctors or intensive care beds or management capacities of individual governors greatly vary. The drawback of even such a partial political decentralization is the lack of policy coordination that might ensue. Even though the term “virus sovereignty” (alluding to the parade of sovereignty in the Russia of the 1990s) is overblown, the monitoring of the “Peterburgskaya Politika” foundation provides a rich overview of regional anti-pandemic measures which it classifies in high, middle and low depending on the degree of regional lockdown.

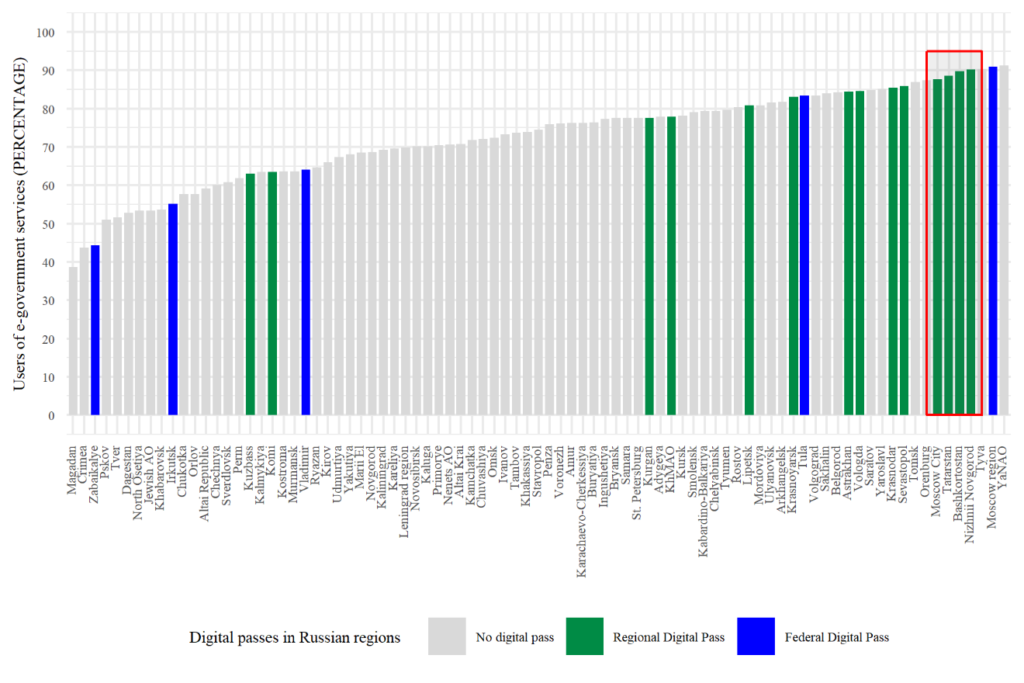

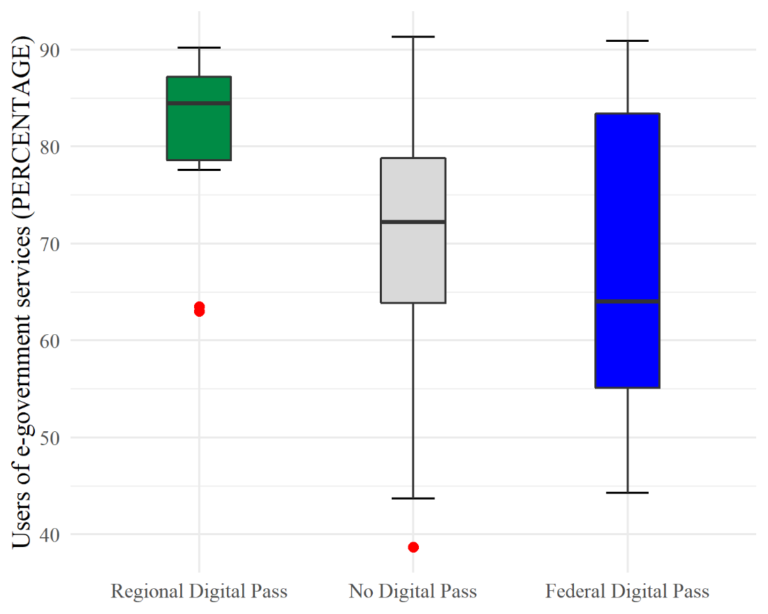

One specific policy reaction that illustrates regional policy experimentation and innovation well are digital passes that were introduced to monitor the compliance of citizens with stay-at-home orders. While Moscow’s digital permits certainly drew the most attention, the patchwork of digital and non-digital approaches to monitor lockdown measures might be indicative of both governance capacity and governance legitimacy. Even though one might conjecture that authoritarian regimes are keen to quickly expand control over its citizens by digital surveillance in crisis situations, the Russian case appears to point to a different mechanism: Particularly regions advanced in providing e-government services to its citizens such as Tatarstan, Nizhnii Novgorod or Moscow City moved fast to introduce digital passes by applying regional technological solutions (Figure 2 and 3).

On 22 April, the federal Ministry of Digital Development and Communication announced that 21 regions would introduce digital passes based on a (hastily developed) federal app. But by mid-May, when lockdown measures were announced to be gradually eased, only 5 regions had opted for the federal application. The large majority of regions did not opt for digital passes or had actively resisted such a federal policy for a range of reasons instead (the pandemic is under control, it is too expensive, or technically too complicated or insecure to implement). The regional policy experimentation points both to a lack of coordination, apparently driven by a lack of political will, to implement a coherent monitoring of lockdown measures. Partly, this is because there are trade-offs between governance capacity, or making use of the capacity, and governance legitimacy.

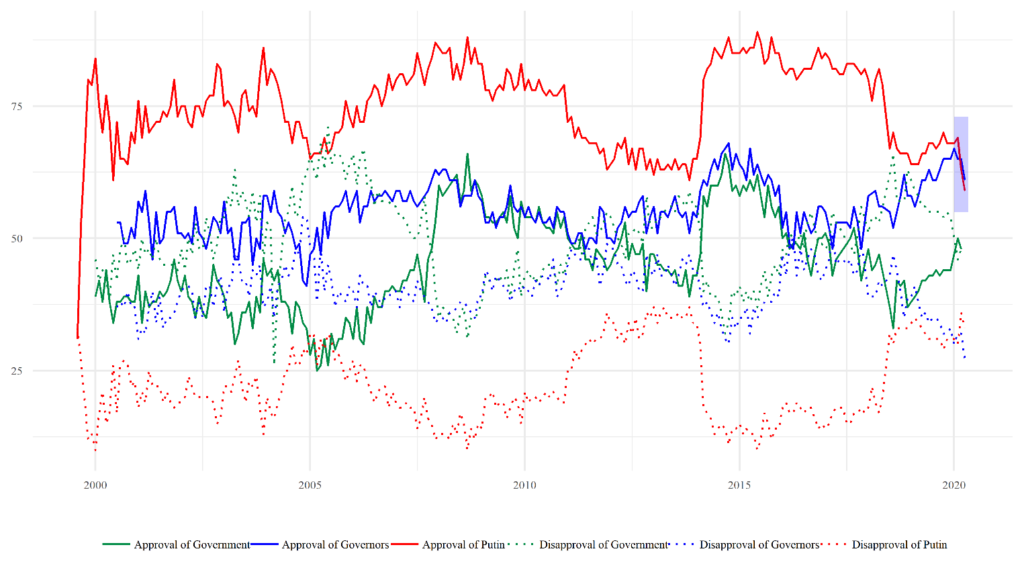

So far, researchers like Zavadskaya et al. make a convincing case that the executive’s reaction to the pandemic is part of a blame game in which the Kremlin intends to shift costs, responsibility and therefore also blame to regional governors. Due to long-term trends in public opinion, however, this strategy by president Putin is unlikely to be successful in the long run. For the first time, the approval ratings of governors, on average, have been higher than those of Putin’s in March and April (Figure 4).

Source: Levada Center https://www.levada.ru/indikatory/

While it remains to be seen what exactly had the most severe effect on approval ratings of the federal and regional executives, it might be presumed that the population is likely to put more blame on those governors who implemented strict monitoring measures including digital passes. If past crises after 2008 and 2014 and their management by the Kremlin are of any guidance for the current pandemic, even when policy measures are driven by an apparent lack of coordination and bad governance, the Kremlin knows how to strike a balance to cope with issues related to trade-offs between governance capacity and legitimacy. But this will depend on how much different the current crises will end up to be from previous ones.

This text first appeared on pex-network.com.

Featured image: kremlin.ru / CC BY 4.0

Kommentare von Fabian Burkhardt